Table of Contents

Infostealers like Atomic MacOS Stealer (AMOS) represent far more than a standalone malware. They are foundational components of a mature cybercrime economy built around harvesting, trading, and operationalizing stolen digital identities.

Rather than acting as the end goal, modern stealers function as large-scale data collection engines that feed underground markets, where stolen credentials, sessions, and financial data are bought and sold to fuel account takeovers, fraud, and follow-on intrusions.

What makes these campaigns particularly effective is their highly opportunistic social engineering approach: attackers continuously adapt to technology trends, abusing trusted platforms, popular software, search engines, and even emerging AI ecosystems to trick users into executing malware themselves.

This combination of industrialized data monetization and adaptive social engineering has made infostealers one of the most reliable and scalable entry points in today’s cybercrime landscape.

In the new 2026 Enterprise Infostealer Identity Exposure report, Flare researchers highlight the growing dominance of infostealers within the cybercrime economy and the expanding impact of identity exposure on organizations.

In this article, we examine the AMOS infostealer as a case study, exploring its evolution, operational model, and real-world activity across its active years.

How Do Infostealers Work?

Infostealers operate as one of the most critical enablers in the modern cybercrime kill chain because they transform a single infection into large-scale credential, session, and identity compromise.

In general, once executed on a victim machine, an infostealer rapidly enumerates browsers, system credential stores, crypto wallets, messaging apps, and local files, extracting authentication data, session cookies, and sensitive documents before exfiltrating them to attacker-controlled infrastructure.

ClawHavoc – The Most Recent Campaign

Recent research by Koi security reminded us that AMOS infostealer dissemination techniques are cunningly designed to find weaknesses and exploit every segment of technology users to steal their credentials.

The research describes ClawHavoc as a large-scale supply-chain campaign targeting the OpenClaw and ClawHub ecosystem (A very popular personal AI assistant) by poisoning the skill marketplace itself.

While the specific details are impressive, what matters more is the underlying tactic. AMOS distributors are capitalizing on OpenClaw’s popularity as AI-hyped software.

As users rush to install it for personal or organizational gains, attackers see an opportunity to bundle AMOS malware within it to steal valuable PII, credentials, and sensitive data.

The delivery model: attackers uploaded skills (OpenClaw add-ons) that looked legitimate: crypto tools, productivity utilities, YouTube helpers, finance or Google Workspace integrations, etc.

Once installed, the malware could steal credentials, crypto wallet data, browser sessions, SSH keys, and other sensitive data, highlighting how AI agent extension ecosystems can become high-impact distribution channels when marketplace vetting is weak.

This is the latest campaign, let’s remember how it all started…

Flare tracks over 1 million new stealer logs weekly from dark web markets and Telegram channels.

Detect compromised credentials, active session cookies, and corporate access before threat actors weaponize them in account takeover attacks.

Start Free Trial

AMOS the Malware – First Sighting of AMOS

AMOS first appeared around May 2023 on a Telegram channel.

Stating its capabilities, which include exporting passwords from the Mac keychain, file grabber, system info, and macOS password exfiltration, browser session theft, crypto wallet data theft with various infostealer management capabilities (web-panel, tests, Telegram logs, etc).

Back then, the cost was $1000 per month, paid through USDT(TRC20), ETH, or BTC.

Since then, AMOS infostealer has become a part of the underground ecosystem, threat actors are willing to buy stealer logs that were extracted from infostealers (such as AMOS) in order to use them as an initial access to their own nefarious business.

For instance, below you can see that a Russian-speaking threat actor dealing with Crypto wallet theft is looking for relevant AMOS logs.

View in Flare – sign up for a free trial to access

AMOS Modus-Operandi

Traditionally, AMOS is disseminated like every known and popular infostealers, such as phishing links, phishing emails, trojanized installers, and click baits, but throughout recent years we have also seen some more noticeable campaigns.

Targeting LastPass Users

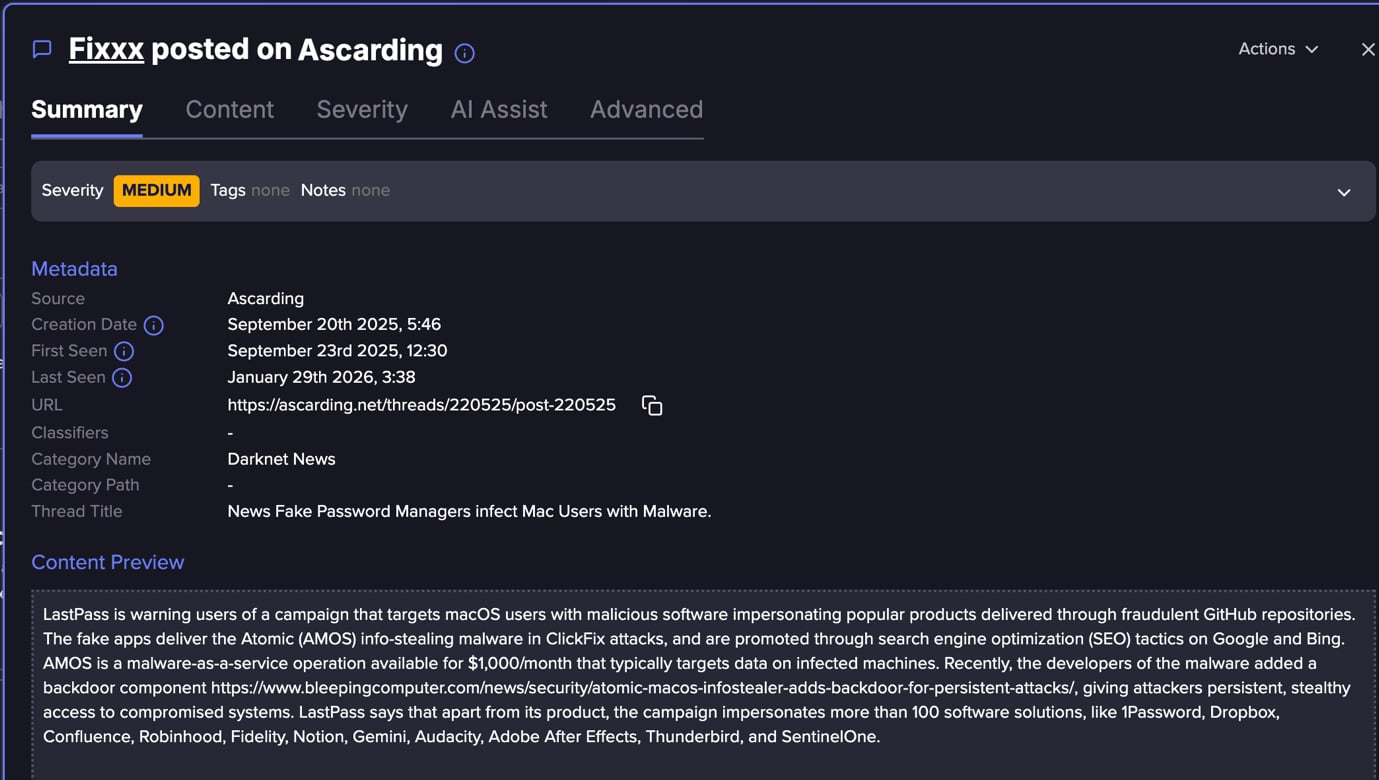

In an underground forum, we saw a post about LastPass that warned of an ongoing AMOS campaign.

This campaign was targeting macOS users through fake applications distributed via fraudulent GitHub repositories, where attackers impersonate over 100 well-known software brands to increase legitimacy.

The operation relies on SEO poisoning across Google and Bing to push these malicious repositories into search results, ultimately leading victims to ClickFix-style pages that socially engineer them into pasting Terminal commands, which download and execute the AMOS payload.

The campaign is particularly resilient because attackers continuously generate new GitHub repositories using automated account creation, highlighting how trusted developer platforms and search engines are increasingly abused as scalable malware distribution infrastructure.

AI-Driven Dissemination Channels

ClawHavoc wasn’t AMOS’s first AI campaign. In December 2025, Huntress reported that AMOS is targeting ChatGPT users. The threat actors used the ChatGPT shared chat feature to host malicious “installation guides” directly on a trusted domain (chatgpt.com), making the lure significantly more convincing.

Victims are driven there mainly via paid search ads (SEO poisoning/malvertising) promoting a fake “ChatGPT Atlas browser for macOS”, then instructed to run a one-line terminal command, effectively turning the user into the execution mechanism.

This example shows yet again that threat actors are weaponizing AI content hype as part of their malware distribution.

Traditional Dissemination Channels

Modern macOS infostealer campaigns rely heavily on social engineering–driven distribution rather than technical exploits. Threat actors commonly create fake installers for popular software such as Tor Browser, Photoshop, or Microsoft Office, packaging malware inside realistic-looking DMG disk images.

In parallel, they use malvertising through platforms like Google Ads to drive victims to spoofed download sites that closely mimic legitimate vendors.

For example, users searching for legitimate software may be redirected to look-alike domains hosting malicious installers that silently deploy stealers such as AMOS.

Another growing tactic is the use of instruction-based execution techniques (often called ClickFix), where victims are guided to run commands themselves in the macOS Terminal.

Instead of exploiting system vulnerabilities, attackers rely on convincing installation instructions, which ultimately execute the malware payload. For instance, asking users to drag files into Terminal or paste commands.

Together, these methods reflect a shift toward abusing user trust, brand impersonation, and legitimate distribution channels to bypass traditional security controls and increase infection success rates.

The Underground Economy Model

The AMOS ecosystem operates as a structured Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) supply chain, where the developers (often tracked in underground forums as AMOS sellers or affiliates) provide the stealer platform, updates, infrastructure components, and sometimes management panels for a subscription cost historically advertised around ~$1,000 per month, typically paid in cryptocurrency.

Downstream threat actors purchase access to the stealer kit, customize lures or distribution channels (malvertising, fake installers, phishing, SEO poisoning, supply-chain abuse, or social engineering campaigns), and focus on maximizing infection volume.

The primary output is a list of stolen credentials, PII, and session logs. This becomes a tradable commodity in underground markets.

These stealer logs are purchased by secondary actors such as access brokers, account takeover specialists, and crypto cash-out operators, who use them for follow-on operations, including SaaS account compromise, financial fraud, ransomware initial access, or cryptocurrency theft.

This multi-stage monetization model turns AMOS infections into a repeatable revenue pipeline, where each actor in the chain specializes in development, distribution, or monetization, reflecting the broader industrialization of the modern infostealer economy.

Unlike traditional malware that focuses on persistence, defense evasion, lateral movement, or destruction, infostealers prioritize speed, data coverage, and stealth, allowing attackers to quickly convert stolen data into usable access.

The resulting “stealer logs” are then sold or traded in underground markets, where other threat actors use them for account takeover, lateral movement, fraud, or follow-on attacks, defacto making infostealers a foundational data-supply layer for the broader cybercrime economy.

The distributor layer is where we typically see the “innovative” or “creative” side of these campaigns – and it’s what usually makes the headlines. This is the layer behind narratives like “AMOS is now targeting AI apps” or “AMOS campaigns are hitting LastPass users.”

In reality, the core malware developers often remain consistent, occasionally adding a new feature or improving packaging and evasion, but the underlying capability set changes incrementally.

The downstream log consumers also tend to operate with established, repeatable monetization techniques.

The distributors, however, are the ones driving real campaign evolution: they decide who to target, define campaign scope, choose distribution channels, and continuously refine the psychological and social engineering techniques used to manipulate victims as part of their operational playbook.

Learn more by signing up for our free trial.

Sponsored and written by Flare.